The pre-Reformation World in Dublin & Glendalough: Alen Register digitised

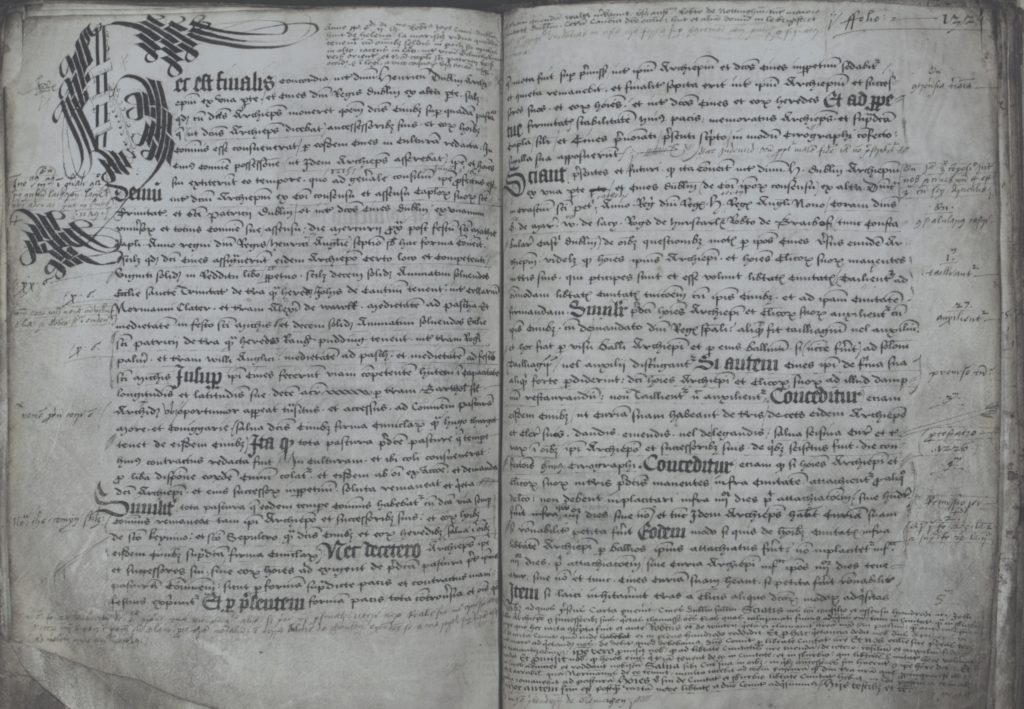

As the RCB Library continues its efforts to digitize and make more resources available to a worldwide audience, a second of its most significant medieval manuscripts: the Liber Niger Alani being the record of John Alen (c.1476-1534), Archbishop of Dublin and Glendalough, 1530-34 (RCB Library D6/3) is now digitally available for public consultation on the Church of Ireland website.

Previously the Library has released a digital version of the Red Book of Ossory – a diocesan administrative record of international renown, which is now complemented by the digital version of the Alen’s “Dublin” register.

John Alen (Alan, Allen), Archbishop of Dublin and Glendalough, 1530-34, was born in Norfolk c.1476. He studied first at Cambridge and completed his Masters in Oxford in 1498, becoming ordained on 23rd February 1499. Admired for his sharp mind in both ecclesiastical and civil law, he rose quickly through the ranks of the clergy, culminating in his appointment as archbishop in 1530. After his consecration in the diocesan cathedral of Christ Church Dublin, Alen immediately began compiling documents for what would become known as “Alen’s Register”, also known as the Liber Niger Alani, early after his arrival in Dublin. He wanted a record of all the lands and properties held by the dioceses. The earliest records he accounted for reached back as far as the conquest of Ireland in the 12th century and continue up to his own administrative era in the 1530s.

The volume is representative of Alen’s ambitious reforms which threatened the position of established powerful families in Ireland like the Fitzgeralds. On 28th July 1534, Archbishop Alen was murdered –his death being one of the opening acts of the Silken Thomas rebellion. On the evening of 26th July, the archbishop had fled the capital, boarding a ship at Dame Gate to escape the rebellion. Unfortunately, he didn’t make it past Clontarf where the ship ran aground. He retreated to allies in Artane but was betrayed and captured there by Thomas Fitzgerald, Lord of Offaly, and several dozen of his men. Alen’s execution was ordered and the items he had with him were seized. Fortunately his register was not with him when he was captured, and neither was it seized when Cromwell ordered that Alen’s remaining valuables be seized as a tax for the Crown. Instead it seems to have remained safely housed along with the diocesan records at the archbishop’s palace, and is now secure with many of those records in the custody of the RCB Library, accessioned as D6/3. Now, some 485 years after Alen’s death, it has been digitized to make its extraordinary content more accessible.

To accompany this significant digital release, topical analysis is provided by Julia McCarthy, a former undergraduate student at Trinity College Dublin, who worked in the RCB Library as an intern during the summer of 2017. Julia also transferred index cards cataloguing the Irish Huguenot Archive to a searchable database previously featured and permanently available for research enthusiasts.

Her analysis shows how Alen’s Register opens a window to pre-Reformation Tudor Dublin. And in an additional paper on the content of Alen’s Register, one of the leading Reformation experts, Dr Jim Murray, demonstrates the circumstances of how the diocese of Glendalough was officially linked to that of Dublin by papal decree of Pope Innocent III in 1216, within a significant pan-European context of pilgrimage and hospitality.

Before 1216, the diocese of Dublin had been largely confined to within the city walls with that of Glendalough designated to outlying lands. Dr Murray’s paper explains in detail how Alen’s transcription of Pope Innocent III’s decree that the union of the bishopric of Glendalough and the archbishopric of Dublin dateable to c.1216, was conditional on the foundation of a hospital by Archbishop Henry de Loundres (Archbishop of Dublin 1213-28). It was ordered that this place of refuge was for the use of the poor and pilgrims, especially those intending to travel to the shrine of St James the Apostle in Compostela on the European mainland. It was intended that this religious hospice might become a community for those wishing to take pilgrimage along the Camino da Santiago through France and Spain.

Ordered to be dedicated to St James and built ‘without Dublin on the seashore which is called Steyn’ (extra Dublin quod in littore maris quod dicitur Steyn), the place designated for the hospital provided a suitable embarkation place for pilgrims waiting for suitable sea conditions and weather to begin their journey to the shrine of St James. The Steyn was an area outside the walls of the medieval city in what now forms the area between the Pearse Street-side of Trinity College Dublin down to the river Liffey, including such streets as Townsend and Poolbeg) and thus in close proximity to the sea.

The story of the Hospital of St James in the Steyn represents just one tiny piece of an extraordinary medieval history revealed by this source – all the more significant in the context of 800 years of united diocesan history, which in its current context has organised an annual Camino de Glendalough through the beautiful Wicklow Mountains, taking in many ancient pilgrim routes to the monastic city of Glendalough along its route. For further information, see this link: http://bit.ly/2Ykxyfd

To view the digitized version of the Register of Archbishop John Allen (c 1476-1534), including the muniments of the diocese of Dublin and Glendalough from c. 1172-1534, © RCB Library Dublin, D6/3, click here: https://issuu.com/churchofireland/docs/alen