The Bank Holiday read: The Gazette’s coverage of Disestablishment in 1869

Drawing on the rich resources of the digitized and freely searchable Church of Ireland Gazette, Dr Miriam Moffitt has produced a timely analysis of the coverage of the Disestablishment story as it happened and was reported by the Gazette, the Church’s newspaper, then under its former name: the Irish Ecclesiastical Gazette (and then as now a monthly, not weekly publication). She focuses on the period between the circulation of the draft Bill in January 1869 to its passage into law on 26th July and then the immediate aftermath to the end of that year demonstrating how the news was reported and thus read and interpreted by the wider Church of Ireland community.

She comments: “At the start of August 1869, exactly 150 years ago this month, members of the Church of Ireland were coming to terms with the news that their Church had been disestablished by Parliament at the end of July. Viewed from today’s perspective, the passage of the Irish Church Bill through both Houses of Parliament was inevitable but few people saw it that way in 1869. Many Irish Protestants accepted that, with a hefty majority of 110, Gladstone’s Liberal government could push through any legislation it chose through the Commons. They had, however, pinned their hopes on the House of Lords where they believed Conservative peers, under the leadership of the Belfastman Lord Cairns, along with bishops from Ireland, England and Wales, would reject the Bill. However, although many of the Lords firmly opposed the Bill, they voted it through, and many of the English and Welsh bishops abstained.

“To have rejected it would have caused such a constitutional crisis that the future of the House of Lords would have been called into question. Members of the Lords could only save one skin – their own or the Church of Ireland’s and, unsurprisingly, they plumped for their own. The acquiescence of the Lords in late July was a bolt from the blue for members of the Church of Ireland who had been told repeatedly that Disestablishment would never happen. The legal status of the Church as the Established Church of the country was defined and guaranteed in Article 5 of the Act of Union of 1800. To disestablish it was to fly in the face of the constitution. It would, and could, never happen. Until it did.”

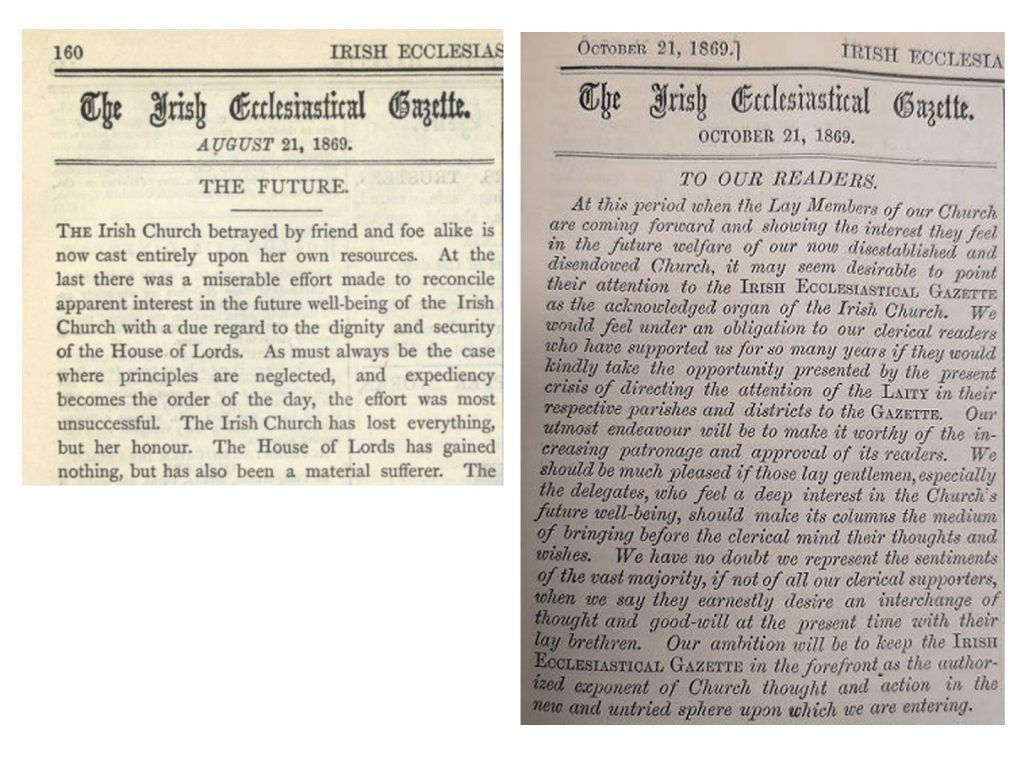

Illustrated with relevant extracts from the newspaper, Dr Moffitt reconstructs the rather late dawning of realities for the Church at large. At the start of 1869, the Gazette had confidently insisted the Church would retain its established status. The January issue assured readers that should the Bill ever reach the Upper House, “the eloquence and logic of such prelates as the Archbishops of Canterbury and the Bishops of Oxford, Peterborough, and Derry would go far towards quashing it”. The absolute conviction that the Bill would be rejected was echoed in the ‘No Surrender’ headline over the 18th February editorial. Again by 21st July – just three days before the Irish Church Bill was finally approved – an editorial confidently insisted: “There is every probability, as far as we can judge at this date, of its falling through”. By 21st August, the tone had changed: “We have been grossly betrayed”.

The online presentation then goes on to analyse the immediate aftermath once Disestablishment became a fait accompli. Again Dr Moffitt’s forensic attention reveals how quickly the focus immediately turned to the future. The Gazette urged its readers to look forwards not backwards: “As long as their seemed a vestige of hope, we hung up the flag of ‘No Surrender’; we have only taken it down when fairly beaten in the struggle. Now, as faithful members of the Church of Christ, it is our duty to accept the issue, bitter as it is, and bend all our energies towards making the best of our new situation. The future of the ‘Irish Church’ depends in a large measure upon a single twelve months.” (Irish Ecclesiastical Gazette, 21st August 1869).

Other aspects of the story, including the deliberations negotiated in private by members of the episcopate in the background, and the role of influential members of the laity who navigated the Church’s more public journey to re-structure itself in the post-established world are also covered. Dr Moffitt observes how most of the negotiations in Westminster were carried out by prominent laymen who were also pivotal in organising the governance systems of the disestablished Church. Their actions ensured that planning was under way to provide an adequate form of church governance whether the Church was disestablished or not and on 30th July 1869, less than a week after the Act became law, this embryonic governing entity was given a name: ‘The Representative Church Body’.

The presentation, which draws on other complementary resources available in the Library in addition to the newspaper, once again reveals how looking through the lens of the Gazette hidden aspects of the Disestablishment story can be recovered. The Gazette is especially useful in recording the diverse opinions held within the Church and, in this instance gaining insight to the different ways in which churchmen experienced a very significant change to their Church and how they responded. There is no evidence, for example, that women were involved at all in the Disestablishment episode. The content of the Church of Ireland Gazette (Irish Ecclesiastical Gazette to 1900) from 1856 to 1949 may be explored in full by using the search box on link to the digitized version of the Gazette available here: https://esearch.informa.ie/rcb

The presentation and supporting images draw on other complementary resources available in the Library.