The Content of Church of Ireland Pew Registers, c. 1719-1839

The online exhibit ‘Please Be Seated: The Content of Church of Ireland Pew Registers’ focuses on the relatively rare church record called the pew register, one of an array of record types produced by the parish vestry – the committee that managed the parish (then as now) in the course of its administrative business.

The parish vestry was responsible for a wide range of civil as well as religious activities. In some of the larger city parishes, for example, until the late 18th century this even included policing the parish, in the form of the parish watch examined in detail at this link: www.ireland.anglican.org/news/6350/the-earliest-policing-records-in

RCB Library administrator, Robert Gallagher, looks at the unusual phenomenon of how, in certain parishes, the practice of purchasing, renting or being assigned with a pew was administered by specific parish vestries. This system was primarily found in wealthier parishes, particularly in urban areas, where parishioners were more likely to be able to afford the cost. Pews were considered as property and, as with all property, it was necessary to record the rights and transactions involving them. In many cases, the record of such transactions was simply kept in the regular vestry minute books of the parish but occasionally, particularly in well-endowed parishes with revenue to spend on dedicated volumes, a separate pew register might be kept.

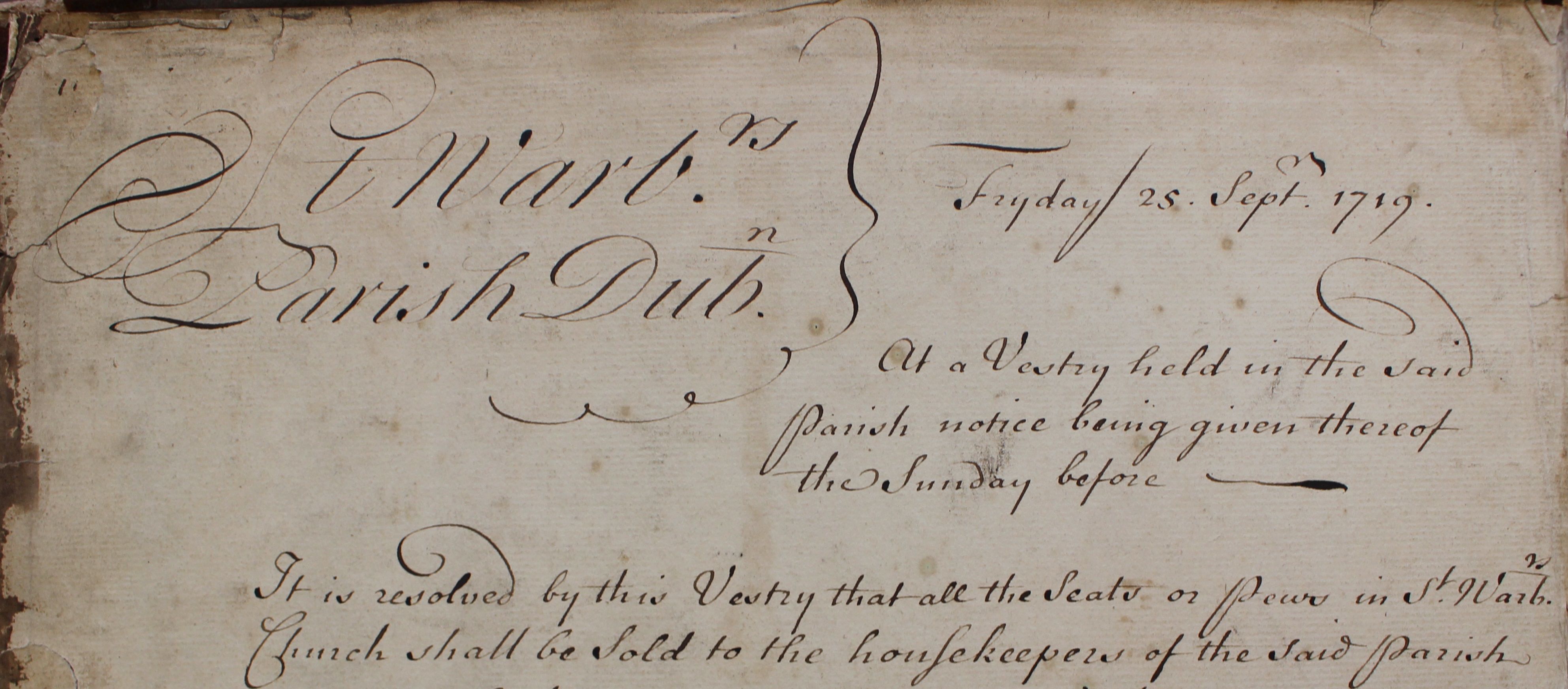

The new presentation examines the content of the pew register of St Werburgh’s in Dublin, a volume spanning the period from 1719 up to 1839 (although after 1764 entries are very cursory indeed, reflecting how the process of owning or renting a pew began to die out in the late 18th and early 19th centuries). As one of the earliest Anglo-Norman churches established within the city walls and as the parish serving Dublin Castle, St Werburgh’s enjoyed a prominent position in the city. Its pew register gives an unusual insight into the parish’s social structure, providing glimpses of the wealth and status enjoyed by the parishioners.

Owning a pew in St Werburgh’s, Dublin, was a lucrative privilege especially for a person who was able to afford one of the more expensive or well-positioned pews, in a parish whose members included the Lord Mayor of Dublin, the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, and some of the leading businessmen in the city such as David La Touche. The volume reveals the resolutions that the vestry agreed about pew-related transactions, the income realised from the same, and the parish’s wider social structure – indicated by such details as who was sitting where – with the most sought-after pews being located either in the gallery or near the front of the church.

While pew registers may be relatively rare, those such as this that do survive provide a colourful asset for researching parish history and the stories of individual parishioners, revealing again the wider responsibilities of the Church of Ireland vestry during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, and the value of the Church’s records as part of social history.

To view the online exhibition, please see: www.ireland.anglican.org/library/archive