The Leinster Tragedy: Human Interest Stories brought to life by the Church of Ireland Gazette and Other Sources

To mark last week’s 100th anniversary of the sinking of the RMS Leinster – torpedoed and sunk just one month before the end of the First World War – the Representative Church Body Library has compiled an online exhibition entitled “The Leinster Tragedy: Human Interest Stories brought to life by the Church of Ireland Gazette and Other Sources”.

The Leinster, a Royal Mail steamer, had departed from Carlisle Pier in the port (and parish) of Kingstown (Dún Laoghaire) on Thursday, 10th October 1918. About an hour later, within sight of the shore, she was fatally struck twice. Current research shows that there were 803 persons on board – 75 crew and 728 passengers: 22 postal sorters, 200 civilians and 506 military personnel. A staggering 564 persons perished, the greatest ever loss of life in the Irish Sea. Eye-witnesses recalled the explosion following the second hit and, within a very short time, the ship went down. Some persons were killed by the blast, some later died from their injuries, some died from drowning, and some were rescued. The Dublin hospitals and morgue were soon full to bursting point with relatives frantically seeking to identify their loved ones.

Collaborating with the historian Dr Miriam Moffitt, who has written the text, and with further input from Philip Lecane, the historian and author of Torpedoed!, and significantly, descendants of some of the people on board, the exhibition focuses on the tragedy from a Church of Ireland perspective. Many casualties had strong connections with the Church of Ireland and the impact of the episode was felt in parishes the length and breadth of the country.

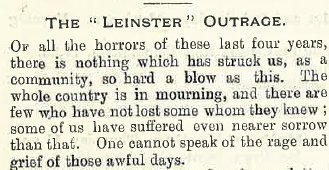

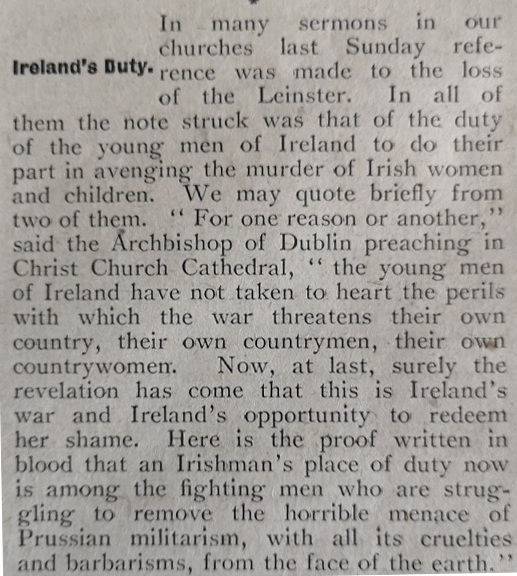

The Church of Ireland Gazette (the Church’s weekly newspaper) in its lead article of 18th October 1918 recorded how ‘[in] many sermons in our churches last Sunday reference was made to the loss of the Leinster’. Under the stark and simple banner headline titled ‘The Leinster’, it reflected how ‘[the] appalling tragedy … has moved Dublin as perhaps no other incident of the war’. Conveying the shared sense of public outrage, it continued: ‘The “Mail” has always been regarded as something in the nature of a civic institution in which all share the feeling of possession and of pride; and when the news spread that the Leinster had been sunk, all distinctions of creed and class and party were forgotten … It was universally felt that the blow to the Leinster was a blow to Ireland …’.

Among the sermons reported was that of the rector of Christ Church, Dún Laoghaire (then Kingstown), the Revd John Pim. One of his parishioners, Dorothy M Jones, a voluntary nurse, had perished, and in a bid to offer comfort to her family and all others mourning victims he reflected how two days later, exactly over the spot where the Leinster had been hit and sunk, several in his rectory household as well as other witnesses in Dún Laoghaire had seen what they described as a ‘great cloud Figure, with outstretched arms, which assumed the form of a cross, and, as the sharpness of its outlines passed, seemed to be full of the faces of men and women’.

Other stories held deep within the family-memories of those involved are also included, an example recounted recently in county Cork thus:

‘William Henry Wood was returning on the Leinster to his regiment in England. The story goes as told in Skibbereen that he had met Mrs Elizabeth Ellam from London, mother-in-law of Ronald Hackett the local dentist, who was on a visit to see a newly born grandchild. After the torpedoing of the ship, he found himself near this older lady, whom he recognised as Mrs Ellam, who was badly injured. He endeavoured to save her by helping her cling unto a baulk of timber. After an hour or more they were both rescued, but Mrs Ellam subsequently died of her wounds.’

The exhibition also explores the diversity of responses within the Church of Ireland. Clergy of all denominations were swift to condemn the attack; and some like the rector of Dún Laoghaire had actually witnessed it. Evidence of divergent opinion however, can be seen in the Gazette editorials and other articles. In the 18th October 1918 edition, there is a discernible difference between the tone of the lead article and the ‘Editorial Notes’, which strongly advocated recruitment as a response, insisting that ‘[if] Ireland is to redeem her good name in the world before it is too late her sons have no time to lose. Peace is approaching with giant and rapid strides’. This contrasted with a more nuanced reflected, possibly penned by Warre B Wells which vigorously condemned Germany for the outrage and expressed a hope that the episode would ‘have a direct influence on the present peace proposals’ but did not in any way advocate enlisting. Instead it hoped that the sinking of the Leinster would strengthen the resolve of those engaged in peace talks and would ‘stiffen public opinion against negotiation with the enemy short of dictation’ (Church of Ireland Gazette, 18th October 1918).

Note:

These and other previously hidden stories bringing the events of this time to light are to be found in the new online exhibition, which is supported by the Commemorations Unit in the Department of Culture, Heritage and the Gaeltacht. The Department has previously supported the Library’s exhibitions presenting other aspects of the Decade of Commemorations, including the extraordinary experience of the Church of Ireland Gazette’s editor, Warre B Wells, who remained holed up in the Gazette’s premises in Middle Abbey Street for the duration of the Easter Rising in 1916, featured in “Reporting the Rising: A Church of Ireland Perspective Through the Lens of the Church of Ireland Gazette” (available at http://bit.ly/2DZGgtE) and furthermore in “Good Wishes for the Great Adventure: The Church of Ireland and the Irish Convention, 1917” which uncovers the content of the diary of Rosamond Stephen – the Library’s founding benefactor – and many other resources concerning the Irish Convention, the last all-Ireland assembly attempt to find an acceptable political solution before Partition (available at http://bit.ly/2yeReW7).

“The Leinster Tragedy” may be viewed online from 9th October 2018 here: www.ireland.anglican.org/library/archive